MANIFESTO FOR THE AMERICAN URBAN PARK SYSTEM IN THE 21ST CENTURY

MANIFESTO FOR THE AMERICAN URBAN PARK SYSTEM IN THE 21ST CENTURY, USA [2016]

The American park system requires a reevaluation of the principles under which it has been operating. The system is too rigid and dependant on maintenance to be effective in our evolving cities. New understandings of how landscape and urbanism could be integrated would result in a more effective ecological and functional city.

RESEARCH

aMERICAN TERRITORY AND LANDSCAPE POTENTIAL

The landscaped or park zones within urbanized areas constitute a major component of the city and have been influenced by the development of the land as a whole. American landscape has always been defined by the cultural interactions and interventions that have taken place since the Europeans arrived, including how the land was parceled. The first colonists to the Americas had multiple reasons to demarcate their territory. “Each community faced the joint need to balance the freedoms and physical dangers offered by immeasured space against the safety and social constraint offered by measure, rule, and boundary”(Corner and Maclean, Measures, 7). Following independence, Thomas Jefferson proposed a rational system of grids to create equal sized parcels at an affordable price in order to create a democratic division of property. The Land Ordinance Act of 1785 set this system into use and distributed power equally across space. Ordering the land according to a set of rules allowed for the purchase and development of the land through secure understandings of boundary, but led to extra undevelopable plots being relegated to parks. The railroad eventually became the space and land defining intervention in the 1800’s, crossing America in straight lines defying the system of grids to achieve quick pathways across the landscape making spatial distances shrink. This pattern continued on with the introduction of the automobile with the freeway and the airplane with the airport. Distance could be taken at speed allowing for new ways of perceiving landscapes which had the unintended consequence of limiting the importance of human scale paths. Lands defined by these new geometries were forced upon the native landscape. As these ruled and infrastructural systems become obsolete their influence on the landscape will continue to be felt.

The ecologies that exist on the land also resist the geometric imposition with their complexities and resilient forms, and they have been evolving since the beginning of the Earth. “When some of the photosynthetic bacteria were buried but did not completely decompose, a slight imbalance resulted in the uptake and release of oxygen, which slowly built up in the atmosphere. Thus early life in the form of these lowly, seemingly insignificant mats began to change the entire planet. Free oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere is the result of 3 billion years of photosynthesis and is therefore a product of life”(Reed and Lister, Projective Ecologies, 156). The Earth has been evolving with life since its beginnings. Biomes in the “natural” world have been developing over billions of years with interaction between the life and the environment. “The environment appears ‘fit’ for life because life has evolved to take advantage of the environment and, conversely, has greatly changed the environment at a global scale”(Reed and Lister, Projective Ecologies, 158). The Earth is a complex, dynamic, and evolving biosphere where there has never been a climatic or steady state of the environment; thus humans are a “natural” continuation of this evolution.

Throughout history, humans have engaged with and altered ecosystems by foraging and hunting. The greatest changes to the terrestrial biosphere by mankind happened at the end of the last ice age, 10,000 years ago, with the development of agriculture. This has led to the start of the Anthropocene, the geological epoch associated with human intervention into the planet as the dominant feature. This has resulted in a required differentiation between biomes and the human intervened anthromes for ecological systems. Most of the terrestrial biosphere has been transformed by humans; land that is not directly being used by humans has still been transformed by the matrix of land use around it resulting in novel forms of ecosystems embedded in human landscapes. “While the ecosystems of unused lands embedded within anthromes may often resemble the undisturbed ecosystems of a biome, they almost always exhibit novel ecological patterns and processes, even where never cleared or used directly, as a result of their fragmentation into smaller habitats within a matrix of used lands, the anthropogenic enhancement or suppression of fire regimes, species invasions, air pollution and acid rain, hydrological alteration, and low-intensity human use for wood gathering, hunting, foraging, or recreation”(Reed and Lister, Projective Ecologies, 175). Large scale infrastructures also divide up landscapes into smaller ecosystems that may be cut off from their surroundings. These resultant forms of ecosystem evolve very differently than previous attempts to categorize them would suggest.

During the initial studies of ecosystems a concept of succession was prevalent. When an ecosystem is influenced by an outside force, disturbance, the system returns to an earlier, developmental stage. This stage is both less efficient and less diverse. It would then proceed through a series of predictable developmental stages, succession, to reach a stable equilibrium state of climax. However, current understandings of succession point to the idea of multiple pathways and end states, if an end state is ever reached(Reed and Lister, Projective Ecologies, 224). Human intervention is also considered part of the system, no longer is it considered an external disturbance. These concepts blur the distinction between cultural and natural landscapes. Therefore the work of human intervention into landscapes must look at building frameworks for sustainable development. Understandings of ecosystems point to systems of complexity exhibiting more resilience in the face of disturbance. Urbanized landscapes, especially parks, must develop to become more diverse and therefore more resilient.

Urbanized landscapes are often characterized by the type of vegetation that can be found in them. Vegetation in these urbanized areas falls into three categories: remnant native landscapes, managed functional landscapes, and abandoned landscapes. The greatest area fir park integration is in abandoned landscapes which “consist of post-industrial or post-residential vacant land, and infrastructural edges dominated by spontaneous vegetation, either native or introduced, on relatively poor and often compacted soils”(Reed and Lister, Projective Ecologies, 243). The plants that are able to grow in these environments are maintaining environmental services for the land including, “excess nutrient absorption in wetlands, heat reduction in paved areas, erosion control, soil and air pollution tolerance and remediation, food and habitat for wildlife, and food and medicine for people”(Reed and Lister, Projective Ecologies, 245). Most of the plants are not considered native to the region and were originally brought to serve specific uses relating to conservation, ornamental, or economic values of the time period.

Most of the plants that have thrived in urban environments have done so through preadaptation; the species were adapted to similar conditions in natural environments that have been replicated in urban situations. New infrastructural typologies have occurred in urban environments which allow for new ecosystems to develop with preadapted species. These include: the chain-link fence which provides a safe haven of the germination of seeds and a trellis for vines, vacant lots which are characterized by high pH level soils which allow plants common to the dry, alkaline grasslands of Europe to thrive, the median strip which allows crab grass to grow year round in the warmer microclimate, stone walls which act like limestone cliffs, and pavement cracks which collect rainwater. These forms of urban vegetation are often considered indicators of neglect and the plants which grow are often called weeds, which is only a term for an undesired plant. There is a large potential for these underused segments of the urban landscape to become an even greater influence on the urban environment through careful selection. These zones could serve important social and ecological functions as parks with no maintenance cost. However, this process of selection must be reviewed over time as urban contexts develop.

Time in these urban contexts is visible through the slow process of the development of individual lots within the city. “The aesthetic of the city at present, if one can speak in such terms, results at best from an ad hoc process, where older landscape identities collide relentlessly with the harsh imperatives of land value, development, productivity, and mobility”(Waldheim, Landscape Urbanism, 89). Cities slowly develop based on successive layers of development that rarely include the larger-scale picture of how they will integrate into the city. Current planning does not consider the long-term but instead focuses on short term gains which have resulted in a fragmented landscape without a framework for lifetime development. The landscaped portions are considered as extra that take up space that the city does not and potentially cannot. Understandings of the past and potential futures should be derived from the observation and objective-based visions for design. These visions will necessarily revolve around the development of new infrastructure with park systems as a matrix for long term visions.

Infrastructure is an undervalued land use in the development of urban landscapes; they have been evaluated solely on their technical efficiency while not considering their impact aesthetically, socially, or ecologically. Although ecological improvements are being considered they are not being implemented as thoroughly as they should with minor interventions happening at small scales. The design of the land surrounding infrastructure has been conceived around the views from the road travelling at speed while not considering how the landscape it cuts through perceives it. These infrastructural spaces have become the major public space in the form of sidewalks, pathways, and small squares at stop lights. There should be “a new attitude to infrastructure that goes beyond technical considerations to embrace issues of ecological sustainability, connection to place and context, and cultural relationships”(Waldheim, Landscape Urbanism, 176). These should link the developed land, the infrastructure, and the underused land of the city into greater park systems.

Many areas of cities are underused or not considered in use at all as post-industrial and post-residential sites. “The waste landscape emerges out of two primary processes: the first, from rapid horizontal urbanization (urban “sprawl”), and second, from the leaving behind of land and detritus after economic and production regimes have ended”(Waldheim, Landscape Urbanism, 199). They form over time from the complexities of the city that can be considered very similar to an organism or to an ecosystem and are the direct result of this growth. These waste landscapes have the potential to act as active components in the city. Even contaminated sites that are closed off allow for diverse ecologies to develop and new forms of vegetation to grow. If sites can function as both an evolving ecological preserve and as functional landscapes they would acquire a greater significance and value to the city.

New concepts of landscape as a functional part of the urban environment are starting to be implemented. “No longer a product of pure art history or horticulture, landscape is re-engaging issues of site and ecological succession and is playing a part in the formative roles of projects, rather than simply giving form to already defined projects”(Waldheim, Landscape Urbanism, 269). Landscape has the potential to redefine the boundaries of sites and their relation to bigger parts of the environment, such as rivers. They can function as a means to limit system failure by allowing natural systems some leeway in disturbance to the land. Adaptive management of the environment would allow for systems to develop alongside human growth.

RESEARCH CONCLUSIONS

NEW ARTICULATIONS OF SITE

The scale of individual plots has been defined by the system of rules that set it up and enabled development to start at the beginning. More potentials will be achieved if land use is not confined to sites that are considered static and bounded. The dynamic relationships that take place in all the environments must be allowed to become freeform entities. Urban democratization of space as a concept should be allowed to take one step further into a blending of ownership leading to cross-fertilization of sites to adapt adjacencies into bigger systems. Urban hard edges should be eliminated in order to facilitate these hybridizations of spatial typologies.

INTEGRATION OF ANTHROME MATRICES

In order to create a resilient structure for future habitation the embedded novel ecosystems of anthromes should become more diverse. This diversity would build in complexities that could respond to local conditions and evolve over time. Overlaid matrices of ecological diversity would then interact within the urban and rural conditions generated by humans to create novel territories. These would allow for new forms of infrastructural and urban taxonomies beyond those presented by Peter Del Tredici in his essay The Flora of the Future presented in Projective Ecologies. Preadapted species would evolve over generations to form new variations of anthromes. These anthromes could be integrated into underused land to create urban meadows to create novel functional ecosystems.

CITY AS A FUNCTIONAL LANDSCAPE

The inclusion of novel ecosystems does not exclude new forms of infrastructural growth and would benefit from the inclusion of intense human integration. New forms of communication open up possibilities for lands to be used for multitudes of functions unknown beforehand. Current pedestrian pathways are late implementations designed to take advantage of underused leftovers from infrastructure design. These pathways are not considered as independent spatial sequences which results in their perception being not aesthetically pleasing at the speed actually travelled. Boundaries are found on either side of pathways which restrict movement and even views in order to separate functionality and these should be removed to make land actually desirable to be on. Integrating the boundaries as gradients to create spatial qualities that promote novel forms of urban space should be considered.

These concepts should be implemented into the urbanized environment as strategies for reinterpreting cities’ park systems. A more inclusionary view of the city as part of the park would eliminate edge conditions by blending the two together. Parks of productive function could serve communities in multiple ways such as gardens, solar fields, and greenhouses. The reevaluation of infrastructural designs would enable new networks of park systems to be integrated seamlessly into the format of the urban environment.

case study I: the chesapeake and ohio canal, dc/md/pa

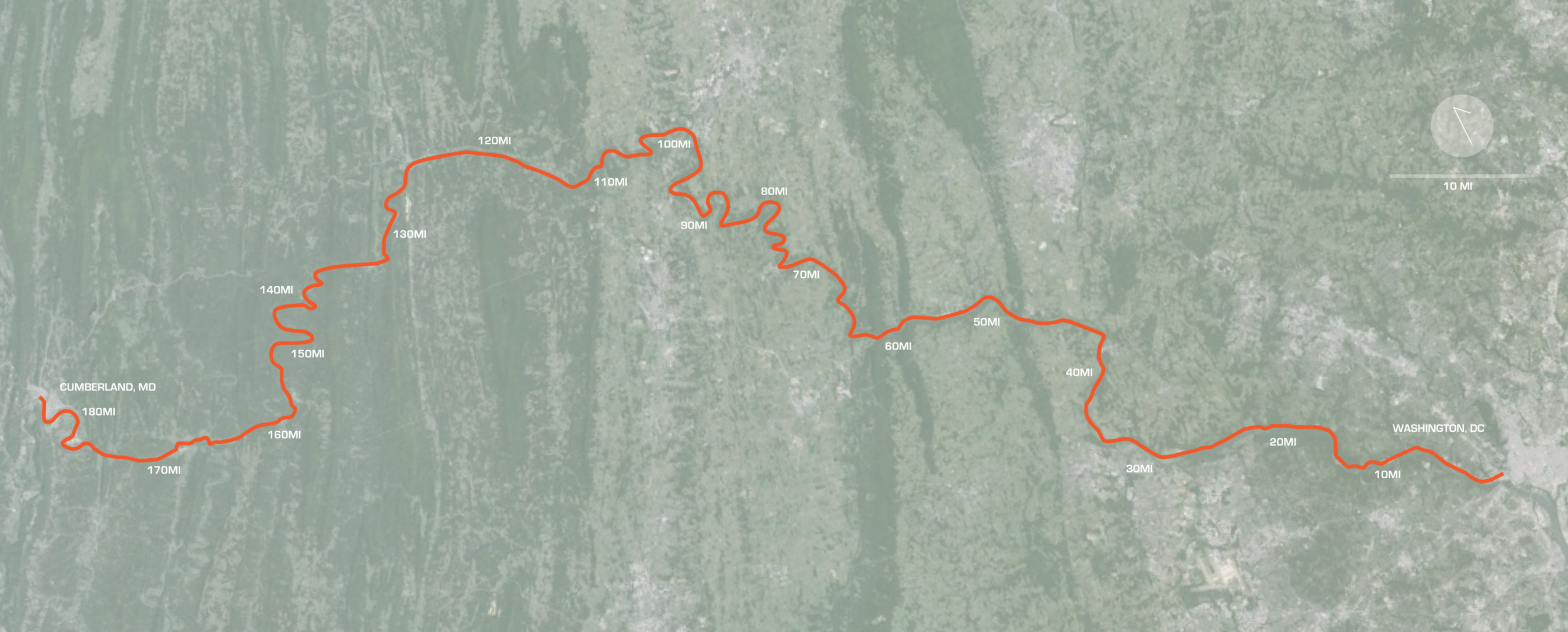

THE CHESAPEAKE AND OHIO CANAL, DC/MD/PA [FIGURE iii]

Plan and vertical elevation change section indicating the extent and length of the canal. DIagram by Cooper Schilder

Paw Paw tunnel [FIGURE i]

Photo by Pat’s East Coast Travel Blog

http://www.patseastcoasttravels.com/2012/05/paw-paw-tunnel.html

canal lock [figure II]

Sketch by Cooper Schilder

existing Conditions

The canal was designed to connect the Chesapeake Bay and the Ohio River, but was never completed. Paralleling the Potomac, the canal was constructed to a length of 184.5 miles, all the way to Cumberland, in 1850. It functioned until 1924, was bought by the US Government in 1938, and became a national park in 1970. The edge conditions within Georgetown are not fully developed along its length and very few businesses are oriented toward the canal. The current trails upon leaving Georgetown look like they aren’t intended for public use. One of the more interesting features further North along the trail is the Paw Paw Tunnel constructed through a mountain to avoid a switch back in the river [Figure I. Paw Paw Tunnel]. The canal locks are also a main attraction feature that dots the park as it winds higher up the river with a total elevation change of 605 feet [Figure II. Canal Lock]. The bridges that cross the canal are interesting focal points as well and attract people to pause along them. The historic structures, of which there are 550, along the canal including the locks and the various historic houses are valuable to the educational aspect of the park.

The park crosses several ecological zones, the Atlantic Coastal Plain, Piedmont Plateau, the valley, and the Appalachian Mountains, [Figure III. Entire C+O Canal Aerial] along its length which adds to its unique biodiversity and connection to the region. The park also features visitor centers and camping. However, due to its length there are issues concerning maintenance, park service coordination and water management. This park has the unique opportunity to be accessed across multiple states at various locations. It functions for light recreation and serves mostly as a passive park that connects different areas. The infrastructural aspect could provide valuable lessons for the development of future infrastructure that becomes obsolete although in its current state it doesn’t seem to be a prime example of the conversion going as well as it could due to the underuse and maintenance issues. The park does not really take a stance toward nature, it is one of ambivalence as a site relegated to be a historical landmark it does not propose to have goals associated with change. The ideal of the park is to preserve the existing as much as possible. The canal does serve a symbolic purpose to the industrial past and as a link between two distant cities.

c+O CANAL PROPOSAL [FIGURE iv]

Diagram by Cooper Schilder

PROPOSAL

The C+O Canal’s former industrial infrastructure inherently tells the story of the park and its former productive capacity and should remain highlighted as the dominant feature. Its immense size allows it the unique opportunity to act as its own ecology that spans across multiple regional anthromes. These ecological concepts aren’t necessarily devoid of the potential for productive capacity within and along the park. Forms of water farming and garden systems could be integrated into the larger system. Sections could be enclosed in greenhouses and non-native but desired species grown. Multiple species could be introduced that are not native and allowed to interact with each other in potentially novel ways to create a new hybrid form of anthrome that might function better for the region. Human intervention should always be kept to a minimum to allow for natural systems to have self-determination. The city should get rid of their current “Views that privilege ideas of harmony, mutuality, interconnectedness, and stability, while overlooking equally natural phenomena such as competition, exclusion, exploitation, disease, and species extinction”(Reed and Lister, Projective Ecologies, 51).

The entire length of the park needs to be better activated by public interaction. The existing bike and pedestrian trails should be augmented with zones of water sports and revamped canal functionality. The overarching goal should be to increase canal usage along its entire length. Some functions that should be included are the greenhouses for microclimates, water sport sections, ecological wetlands, managed farmland, commercial river walk, and swimming pools [Figure IV. C+O Canal Proposal]. Some of these functions might require the widening of sections for new functionality. Businesses should orient themselves to the canal similar to the San Antonio River Walk, especially along the Georgetown segment where a few folding chairs are the only passive interaction with the canal besides the bridges. If more businesses were encouraged to develop along the length of the canal it would promote more usage. Some combination of mobility, relaxation, and functional landscape should be incorporated like a mosaic along the park’s length. Pathways should be upgraded from rough gravel to something more fixed in order to promote more usage. Maintenance should become more decentralized, potentially taken on by local communities based along its length and opportunities for ecological education should be considered.

case study II: hermann park, houston, tx

HOUSTON PARK SYSTEM [FIGURE VI]

diagram by Cooper Schilder

HERMANN PARK ADJACENCIES

Diagram by Cooper Schilder

existing conditions

Hermann Park was founded as a gift to the city to be used as a site for a future park early on in the city’s development by George Hermann. The design of this active park which has developed with additions since its inception has become a conglomerate of competing values. There is a zoo in the south, a golf course on the east and many other functions in the northwest corner of the park. The site is over-programmed with sections becoming invariably weaker due to internal adjacencies and lacks a unity throughout with fences and roads cutting various zones off. It serves as a destination for the city of Houston.

The edge conditions are a major issue with the park; the boulevard on the west does the best job of addressing the connection but is still fairly wide and trafficked. The south and east are the worst connections with the major streets acting as barriers. The adjacencies of the museum district to the north, Rice University to the west, and the Texas Medical Center to the south are all major attractors in the city and the edge conditions of the park detract from it becoming an integral part of the community [Figure V. Hermann Park Adjacencies]. The central road which bisects the park is the main way visitors are intended to approach and a parking lot is located in the center. The park is currently linked to the bayou system of parks, but the connection is fairly weak since it wasn’t planned from the beginning. The golf course is the largest barrier to the connection to the bayou which is channelized and has carefully maintained grass along its length. The park acts as a cultural destination with the role of humankind to the nature being one of control and protection. It should not be applied to the entire city in its current form as it is over programmed and has fenced edges. I do not believe the park has a achieved a symbolic presence in the city as a whole but individual components such the zoo might be considered as such.

hermann park proposal [figure VII]

Diagram by Cooper Schilder

PROPOSAL

The park has a lot of potential to change due to its location; close proximity to major developments and its connection to the bayou park system [Figure VI. Houston Park System]. It is over programmed to the point that there is no unused space for emergent behavior to adapt interstitial spaces. Reducing the active planned spaces would consolidate the park into a matrix with gradients of potential activities instead of strict boundaries between functional zones. The largest detriment to its current state is the golf course acting as a barrier of immense size between the bayou and the central core of the park. The golf course should be removed to create these spaces and to connect the park to bayou which would allow greater connectivity both east and west to other parts of the city. This could create a regional park similar to the Emerald Necklace in Boston. The east in particular is cut off nearly completely, partially due to the highway that runs adjacent to the edge of the park. These edges should blend into the neighborhoods and adjacencies though designed paths and vegetated linkages extending out. The connections through the park also serve as barriers between existing landscapes and would serve the park better if they were transformed into softscape roads demarcated by slight changes to the vegetation and topography. They could potentially even be highlighted through the use of built in lighting marking boundaries or transitional edges to make both pedestrians and drivers more aware.

The typology of the bayou should be redeveloped to incorporate a more naturalistic but no less functional landscape ecology. The link through the bayou should create a more regional park system throughout Houston. The channelized sections of the bayou should become variable width and depth at zones to create more variances between habitats. The ecological reclamation of the waterfront paths could create habitats for wildlife within the city that are lacking partially due to the manicured golf course acreage. However, this ecology should not be focused on recreating the image of what was there before, but as variances of the native natural conditions. “In an urban context, the concept of restoration is really just gardening dressed up to look like ecology”(Tredici, Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast, 12). Therefore new species that are already preadapted should be allowed to create their own succession as a new ecology. By incorporating these ideas the park would function more as a regional asset by linking the disparate communities into a more functional landscape [Figure VII. Hermann Park Proposal].

CONCLUSIONS

THE FUTURE OF AMERICAN PARKS

Landscape should be looked at holistically and as part of a much larger system that is constantly evolving. There is no end state for ecological succession; the anthromes are constantly readapting to evolving conditions. Human interventions in American parks should be focused on culturally inhabitable spaces, ecological reservations, and functional landscapes. The types of parks: passive, active, recreational, nature reserve, and regional, should be combined together to create more inclusive parks with a mosaic approach to use. If the boundaries of property lines, particularly those of parks weren’t so well defined there would be more options for gradient park linkages between larger parks. These should require little to ideally no maintenance in order to function without supervision or funding. The entire city should be viewed and considered as one large park with programmed elements, the structures, placed within. The infrastructure linking these programmed elements should become part of the landscape. I believe these concepts will increase the livability of cities and promote healthier living within them while at the same time serving both the natural environment and the cultural necessities of the urban context.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beck, Travis. Principles of Ecological Landscape Design. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2013.

Berger, Alan. Drosscape: Wasting Land in Urban America. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006.

Corner, James, and MacLean, Alex. Taking Measures Across the American Landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Hanna/Olin Ltd. Renewing Hermann Park: A Comprehensive Master Plan. Report. 1995.

Parsons, John G. Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park District of Columbia/Maryland General Plan. Report. 1976.

Reed, Chris, and Nina-Marie Lister. Projective Ecologies. New York: Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2014.

Stasus (Firm), Craig, James A., and Ozga-Lawn, Matt. Pamphlet Architecture 32 : Resilience. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2012.

Tredici, Peter Del. Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast: A Field Guide. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010.

Waldheim, Charles. The Landscape Urbanism Reader. New York: Princeton Architectural, 2006.